The Maui wastewater case has far-reaching ramifications for the nation’s rivers, lakes and oceans. And it’s headed to a conservative Supreme Court.

Honolulu Civil Beat, August 6, 2019

By Nathan Eagle

Environment

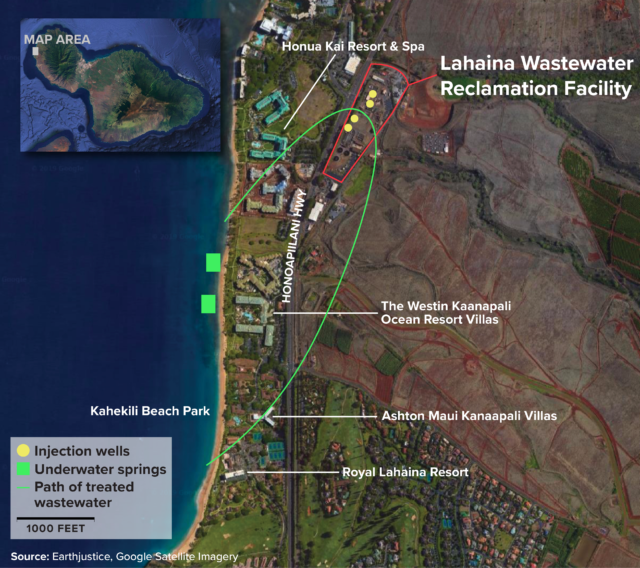

For more than 40 years, Maui has piped wastewater into wells on the west side of the island, treated it to a certain standard and then done nothing as it flows through the groundwater and into the ocean just off the coast of Kahekili Beach.

County officials knew the effluent would follow this course before the Lahaina facility was built in the 1970s. And they know it’s happening now along the resort-lined shore as tourists snorkel through a coral wasteland wondering where all the fish went.

But the county has yet to do anything about it, despite losing repeatedly in court over whether a federal pollution permit is needed.

Now the case is barreling toward a conservative-leaning U.S. Supreme Court, whose decision could carve a massive loophole into longstanding protections for America’s rivers, lakes and oceans.

“The county is being a frontman for a whole villain’s list of the nation’s worst polluters that want to use this case to gut the Clean Water Act,” said David Henkin, a Honolulu-based attorney for Earthjustice, which is representing the four environmental groups who brought the lawsuit.

The Hawaii Wildlife Fund, Sierra Club-Maui Group, Surfrider Foundation and West Maui Preservation Association sued in 2012 after trying for years to reach an agreement with the county to instead reuse the treated effluent on golf courses, farms or commercial landscaping.

They argued that the county should have obtained a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit that is required under the Clean Water Act when polluted water from a known source enters “navigable waters.”

Federal district and appeals court judges have ruled in their favor, rejecting the county’s argument that it did not need a permit since the treated effluent passed through groundwater before entering the ocean — a sort of who-touched-it-last argument.

“To hold otherwise would make a mockery of the CWA’s prohibitions,” 9th U.S. Circuit Court Judge Dorothy Nelson bluntly wrote in the court’s decision last year.

Federal Courts Split

The Lahaina facility serves about 40,000 people and handles 3 million to 5 million gallons of sewage a day. On the low end, the amount entering the Pacific is like installing a permanently running garden hose every three feet along a half mile of coastline, according to court filings.

The treated effluent is generally not harmful to humans. But peer-reviewed studies have shown it has decimated the fringing reef, which is already reeling from warmer and more acidic waters thanks to global climate change.

The nutrient-rich wastewater causes huge algal blooms that smother the corals, which is what sounded the initial alarm in the early 2000s. That means less habitat for fish and endangered sea turtles, but also the breakdown of a natural barrier to protect coastal roads and properties from stronger storms and surf.

“This is something we can do something about,” Henkin said. “When people sometimes get a little hopeless, the name of the game is building resilience. Attacking the input of nutrients and acidic freshwater into reefs is going to make them more resilient and capable.”

Maui County contends that it has just been disposing of pollutants into wells and does not need an NDPES permit because it is not directly dumping the treated wastewater into the ocean; it’s passing through groundwater first, which is not federally regulated.

No one disputes that groundwater is generally the state’s jurisdiction. It’s where the pollution ends up that matters, as judges have ruled in this case.

“Although the County quibbles with how much effluent enters the ocean and by what paths the pollutants travel to get there, it concedes that effluent from all four wells reaches the ocean. The County has known this since the Facility’s inception,” Nelson wrote in the appeals court decision.

But there isn’t a clear consensus among federal appeals courts throughout the country, especially in recent years.

The 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decided the Kentucky Utilities Co. was not responsible for the pollution from its coal-fired power plants that was released into Herrington Lake because it did not happen directly. Leftover coal ash was stored in manmade ponds, seeping into the groundwater before entering the lake.

The 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has felt similarly about coal ash but not about oil. A pipeline owned by Kinder Morgan ruptured in South Carolina, spilling hundreds of thousands of gallons of gasoline, which seeped into the groundwater and then polluted nearby rivers, lakes and wetlands.

In a split decision, the court determined the Clean Water Act applied because pollutants from a known source were added to federally regulated waters. It did not matter that they flowed through groundwater first, so long as there was a clear connection.

‘Trivially Easy To Evade’

The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to take up the Maui case to answer the question. It set a hearing for Nov. 6, and seemingly everyone wants to be part of it.

Last month, a slew of groups filed friend-of-the-court briefs that lay out their positions, generally backing one side or the other.

Maui County has received support from current EPA and Department of Justice officials; oil, gas, mining and pipeline industry representatives; utility companies; property rights groups; iron and steel workers; and almost two dozen mostly red states, their governors and senators.

Among them is Kinder Morgan Energy Partners and Plantation Pipe Line Co., which is 49% owned by ExxonMobil. They essentially make the same argument as Maui. If the pollutant passes through groundwater first before entering federally regulated surface waters, the Clean Water Act should not apply.

The Maui environmental groups’ arguments have been backed by former Republican and Democratic Environmental Protection Agency administrators; craft brewers; trout fishermen; aquatic scientists; law professors; conservationists; a Native American tribe; and a dozen mostly blue and coastal states.

The Craft Brewers group, which depends on clean water as the main ingredient in beer, finds “little sense” in Maui’s argument, saying this would make it “trivially easy to evade” the Clean Water Act, according to the brief it filed last month.

The group’s attorney argues that a factory whose pipe sends pollutants flowing into a river could avoid regulation by moving its pipe into a gravel pit so the groundwater carries the pollutants to the same river.

Others have spelled out similar hypotheticals. What if a pipeline stops just shy of the shoreline, dumping its waste first into the groundwater despite knowing it will pollute the ocean?

In the Maui case, attorneys relied on a tracer dye study that the EPA ordered in 2011 after growing concerned about the Lahaina wastewater system polluting the ocean. Sure enough, when scientists from the University of Hawaii put dye into the injection wells, they documented it less than three months later flowing out of natural underwater springs just feet from Kahekili Beach about a half mile from the facility.

That confirmed what seemingly everyone had known since the 1970s — that treated wastewater injected into the wells would find its way to the ocean.

A 2017 study discovered how much that actually mattered. Scientists found the nutrient-laden water was literally eating the reefs away, orders of magnitude faster than just by ocean acidification and other effects of climate change.

“Our results confirm how valuable nearshore coral reef ecosystems – the cornerstone of Hawaiian tourism, shoreline protection, and local fisheries – are affected by land-based sources of pollution that are also magnified by effects of coastal acidification,” Nancy Prouty and five other scientists wrote in their peer-reviewed paper.

Between all the stressors, the state Division of Aquatic Resources has reported a 40% decline in coral cover off of Kahekili from 1994 to 2005.

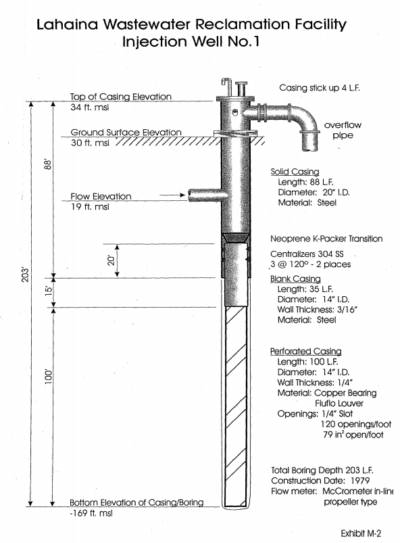

Maui County actually has one permit for its wastewater system in Lahaina. It’s an underwater injection control permit required by the Safe Drinking Water Act. That ensures the water is fine to use on crops, for instance, but it doesn’t regulate the quality for marine life.

Nitrogen levels, for instance, have to be kept below 10 mg per liter under the Safe Drinking Water Act, which is reflected in the county’s underwater injection control permit.

If the county had to obtain an NPDES permit, as the district and appeals courts have ruled, it would have to treat the wastewater to bring the nitrogen levels below 0.15 mg per liter to not kill marine life, Henkin said.

Maui’s elected leaders have so far refused to drop the case, torpedoing settlement offers. The last one, which Henkin said still stands, involved paying a $100,000 fine and putting $2.5 million toward infrastructure to recycle the wastewater.

The county has instead paid more on outside legal counsel than the settlement would have cost. Maui taxpayers are spending $4.3 million for representation by Hunton, Andrews, Kurth.

Elbert Lin, the Virginia-based firm’s lead counsel for the case, did not respond to a request for comment last week.

Maui County Council Chair Kelly King has tried to wrest control from Mayor Mike Victorino, who has followed in the path of former Mayor Alan Arakawa under advice from the same corporation counsel, Patrick Wong. But so far she has lacked the votes.

In May, the council was split 4-4, with one member absent, on a vote at the committee level to recommend the full council approve the latest settlement. The committee’s chair, Mike Molina, who voted against it, has yet to put it back on the agenda.

“This would be a huge stain on the reputation of Maui,” King said in an interview last week.

“It’s a political move to help the Trump administration perpetuate its attack on the environment,” she said. “I have no idea why anyone on Maui would support that.”

She and others who want the case dropped blame scare tactics. Some members of the council and administration worry that losing this case would mean thousands of homeowners with cesspools and septic systems might also be in violation and face fines.

The Hawaii Department of Health sent a letter in June to Councilwoman Tasha Kama to allay those concerns, which has been shared with other council members.

The letter from the state’s deputy director for environmental health, Keith Kawaoka, says the department has no plans to enforce the NPDES permit requirements against existing septic systems and cesspools.

The EPA’s own website makes that clear, too. The agency’s summary of the Clean Water Act says individual homes that use a municipal system, septic system or otherwise don’t have a surface discharge don’t need an NPDES permit.

“There’s been a lot of fear mongering,” Henkin said. “It’s just fantasy stuff.”

Victorino won’t back down though. He was unavailable for an interview last week, but his office sent a statement and sections of the EPA’s latest views on the issue.

The EPA’s stance shifted in April with an “interpretative statement” on the application of the Clean Water Act on the NPDES program when it comes to releasing pollutants from a point source to groundwater.

A spokesman for the mayor highlighted a section that says how the circuit court decisions “potentially sweep into the scope” of common activities “such as releases from homeowners’ backyard septic systems that find their way to jurisdictional surface waters through groundwater.”

Henkin views it as a 180 degree shift in the EPA’s position, noting how it was the EPA itself that was concerned about Maui violating the Clean Water Act.

“This is not Trump EPA versus Obama EPA,” he said. “It’s Trump EPA versus every EPA — the Bush EPA, the Reagan EPA.”

An EPA spokesperson deferred comment to the solicitor general’s friend-of-the-court brief in the Maui case, another document Victorino’s office pointed to.

Noel Francisco, counsel of record for the Department of Justice solicitor general, says in the brief that the Clean Water Act could be interpreted to cover such releases into groundwater that could require some septic tank owners, for the first time, to obtain NPDES permits.

He says the same could be true for those engaging in other common forms of water management, including green infrastructure projects.

In the mayor’s statement to Civil Beat, he touts how much the county plans to spend on recycled water projects in Lahaina and Kihei, but sticks to the administration’s past arguments for proceeding with the case.

| “It’s one of the most important cases going before the Supreme Court in years.” — Stuart Coleman, Surfrider Foundation |

“The Lahaina injection well lawsuit affects the County’s water reuse and disposal systems, as well as private properties with cesspools and septic tanks,” the mayor’s statement says. “This is why it is vital that the U.S. Supreme Court decide whether the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals expansion of the Clean Water Act is accurate or not.”

Victorino said in the statement that the case would have far-reaching consequences, but the concerns he stated were about property owners not the environment.

“The Ninth Circuit ruled that if you can prove that pollutants make their way from a source to the ocean or a river, and don’t have a permit, it is a violation of the federal Clean Water Act,” he said. “This is true for the County’s injection wells and it would also be law for property owners, condominium complexes, and others in the non-sewered makai areas.”

While the county treats the wastewater to a certain degree, the mayor is uncertain if it would meet requirements of a Clean Water Act permit.

His office did not respond to follow-up requests for an interview with Victorino.

King is baffled by the mayor’s and her fellow council members’ reluctance to drop the case. But she has faith in the county eventually fixing its wastewater problems, noting that money has already been budgeted to do so.

“Maui will be OK,” she said. “I worry about other places around the country like Flint, Michigan, that may no longer have standing to bring lawsuits.”

Stuart Coleman, head of the Hawaii chapter of Surfrider Foundation, is similarly concerned about the precedent the case could set.

“It’s one of the most important cases going before the Supreme Court in years because it could set us back so far,” he said.

Coleman still thinks settling the case is the best option, as does his attorney. But it’s up to the mayor and council.

“This is a case that should never have had to go to court in the first place,” Henkin said. “The ball is in their court though. We will see what they do.”

Original article URL:

https://www.civilbeat.org/2019/08/maui-is-taking-this-clean-water-legal-fight-all-the-way-some-say-too-far/