MauiTime, August 30, 2019

By Axel Beers

In 2014, residents of Anderson County, South Carolina, discovered that energy company Kinder Morgan’s underground Plantation Pipe Line had ruptured, spilling hundreds of thousands of gallons of gasoline into groundwater and soil. Much of the fuel made its way into parts of the Savannah River, but concerned citizens and environmental advocacy groups like Savannah Riverkeeper were helpless to hold Kinder Morgan accountable. Until 2018, when after three years of litigation, local citizen groups can won in Circuit Court, affirming their ability to enforce the Clean Water Act against Kinder Morgan’s unauthorized pollution of the waterway.

In the 1990s, Decatur County, a mostly-rural, small county in Tennessee, made the decision to privatize their landfill. The company in charge of managing the site, Waste Industries, found that it could increase profits by accepting “special wastes” deemed “difficult or dangerous” to dispose of. Years later, and after having accepted more than 640,000 tons of toxic smelting byproducts from aluminum companies, Waste Industries tried to walk away from its contract with Decatur County and responsibility for the toxic leachate (“landfill juice”) coming from the landfill and polluting nearby air and water. Decatur County’s lawsuit against Waste Industries is pending.

In Minnesota, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, a federally recognized Native American tribe, gathers fish and manoomin (wild rice) in the same places their ancestors did over hundreds of years. These traditional gathering places are threatened, however, by upstream development of mines, which discharge wastewater contaminated with mercury and sulfate. When these pollutants arrive in the Chippewa gathering places, they kill the manoomin and make the fish toxic for human consumption.

These stories from across the nation are among many found in amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs filed in support of the Hawaii Wildlife Fund and against the County of Maui ahead of oral arguments scheduled in the US Supreme Court on Nov. 6. With one side of the battle, including Anderson and Decatur Counties and the Fond du Lac Band, concerned that a ruling in the county’s favor would “gut” the Clean Water Act’s protections, and the other side saying a victory by the HWF would expand the CWA (and the US Environmental Protection Agency’s power), the federal implications are tremendous, making the case one that’s being watched nationwide by individuals, policy makers, businesses, and advocacy groups. It’s a case years in the making, and one that goes at least as far back as 1973.

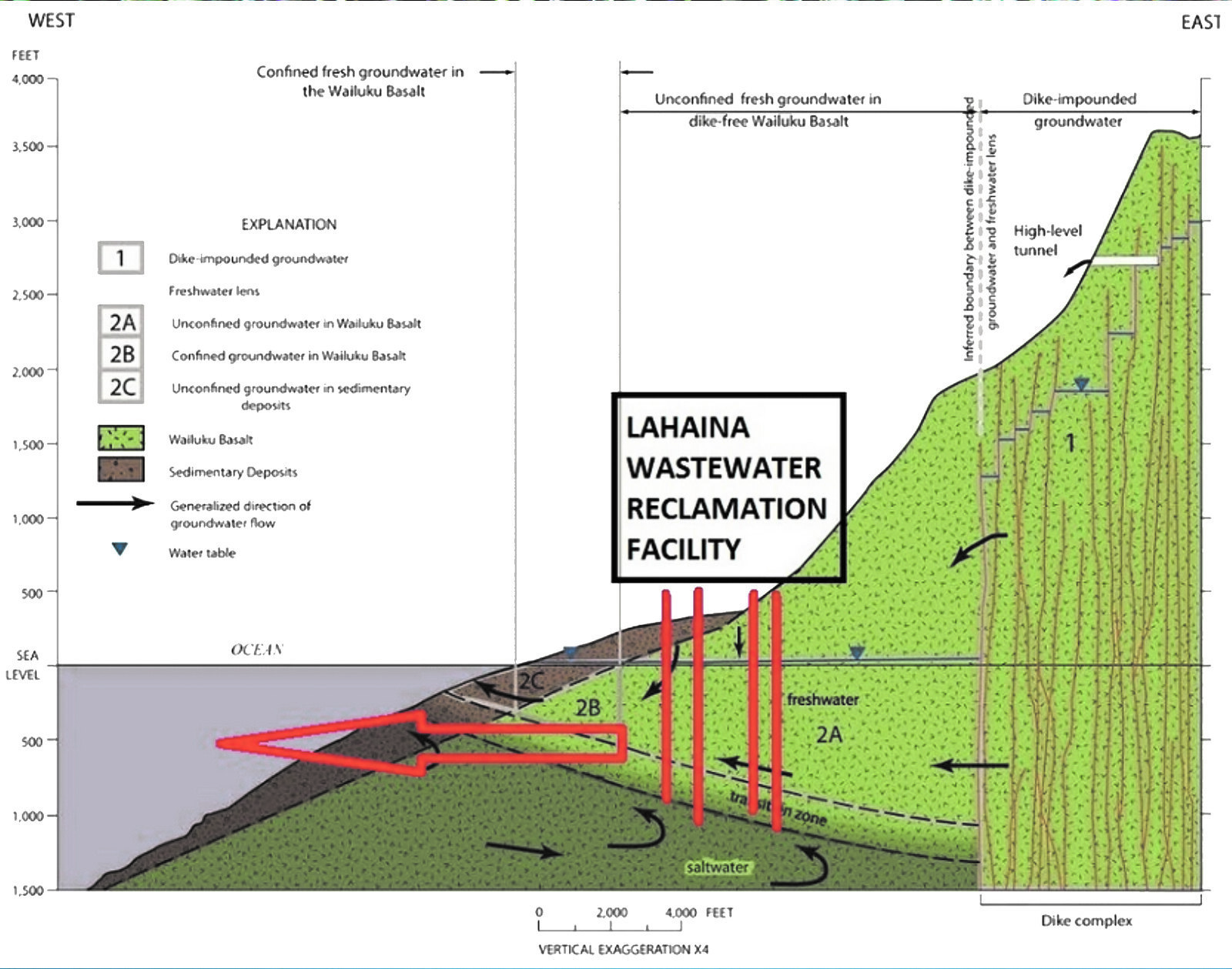

Treated wastewater from the LWRF is injected into underground wells, enters the groundwater, and seeps into the ocean off West Maui

In 1973, the epicenter of the dispute, the Lahaina Wastewater Reclamation Facility, existed as a mere design. When an environmental review was conducted, county consultant Dr. Michael Chun made a consequential statement: He said that treated wastewater, or effluent, would be injected into wells and, significantly, he acknowledged that the pollutants would indeed emerge in the ocean – away from the shore. At the time, it was seen as a desirable alternative to dumping the treated water directly into coastal waters.

Years after the review, the LWRF was in operation, injecting the effluent that couldn’t be recycled into underground wells. And, although the injection wells were originally intended to be used only as a backup method for water reclamation in times of excess, they have since become the county’s primary method of disposing of effluent.

According to 2018 court documents and put simply, that means a lot of doo doo water. The LWRF receives waste from a system serving 40,000 people. The water is then treated, and some of it’s sold for irrigation. But most of it – approximately three to five million gallons per day – is injected into groundwater where it eventually makes its way to West Side ocean waters. On a day of 2.8 million gallons of discharge, a county expert said, the flow of effluent into the ocean is about 3,456 gallons per meter of coastline, or “roughly the equivalent of installing a permanently running garden hose at every meter along the 800 meters of coastline. About one out of every seven gallons of wastewater entering the ocean near the LWRF is comprised of effluent from the wells.”

But the lawsuit isn’t about whether the treated sewage is making its way to the ocean in places like Kahekili Beach – the County of Maui, as Chun did in 1973, acknowledges that this is happening. The question is whether Maui County has the correct permits to allow it to happen.

While the County of Maui has the appropriate Safe Drinking Water Act permit from the state for the discharge of the treated effluent into groundwater, it does not have a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit required through the federal Clean Water Act for discharges into surface water (counterintuitively, the standards for certain pollutants like nitrates are more stringent under the CWA than the SDWA). Essentially, the county doesn’t think it needs an NPDES permit, as the EPA states, “The Clean Water Act prohibits anybody from discharging ‘pollutants’ through a ‘point source’ into a ‘water of the United States’ unless they have an NPDES permit.”

Because the effluent from injection wells travels through groundwater (which the county doesn’t consider a “water of the United States”) before getting to the ocean, the county argues, the injection wells cannot be considered a “point source,” a term defined broadly due to litigation but recently by the EPA as “any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance, such as a pipe, ditch, channel, tunnel, conduit, discrete fissure, or container.”

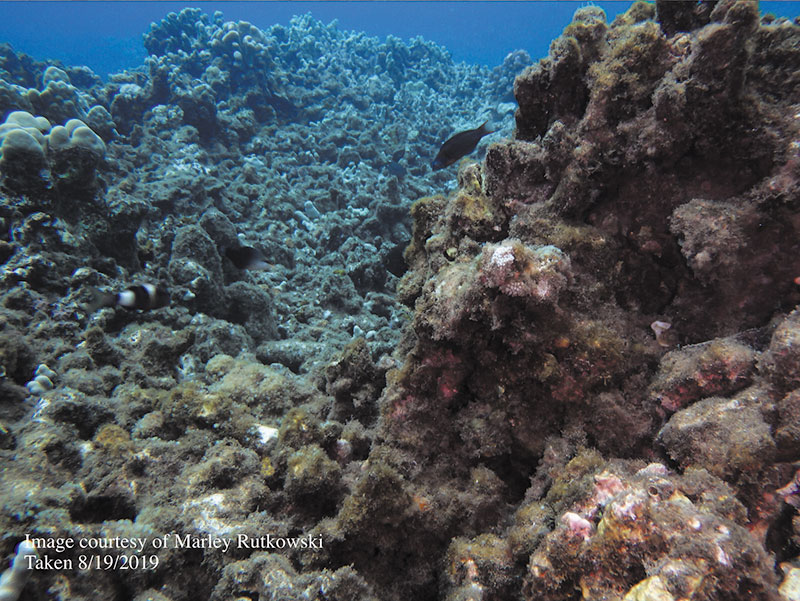

Image of reef off West Maui near effluent seep, taken 8/19/2019

Image of reef off West Maui near effluent seep, taken 8/19/2019

“In conflict with this Court and several courts of appeals, the Ninth Circuit incorrectly expanded NPDES point source permitting to cover nonpoint source pollution, which is regulated in other ways,” stated the county in its filing with the Supreme Court.

Of course, Hawaii Wildlife Fund disagrees, and based on its reading of case law argued points that were later accepted by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which found the County of Maui liable for its injection well practices. “The court based its decision on three independent grounds,” it wrote it its opinion. “(1) the County ‘indirectly discharge[d] a pollutant into the ocean through a groundwater conduit,’ (2) the groundwater is a ‘point source’ under the CWA, and (3) the groundwater is a ‘navigable water’ under the [Clean Water] Act.”

So in the end, the case that is putting Maui County in the spotlight comes down to legal precedent and semantics. It’s clarification that the county thinks is necessary, stating “The Ninth Circuit has created a growing conflict over the distinction between point source and nonpoint source pollution.” Critics of the county’s position argue, however, that the clarification will be swayed toward the preferences of Trump-nominated judges and will only serve to aid in the president’s campaign to roll back environmental protections.

“Maybe now you understand why the county’s supporters are chomping at the bit for the Supreme Court to rule in the county’s favor,” said Earthjustice attorney Mahesh Cleveland at a talk held at the Maui Ocean Center and organized by HWF. “You will give them all a loophole in the Clean Water Act that would enable them to pollute with impunity as long as they use groundwater as their sewer.

“I mean, do you really think the pipeline industry cares about the people Maui? Or the coal and gas industry cares about our reefs? Or that mining and fracking operations care about our beaches being smothered with algae? Of course not; it’s about money and deregulation.”

Sierra Club, Earthjustice, West Maui Preservation Association, and Hawaii Wildlife Fund representatives present petitions signed by 15,962 individuals asking the County Council to settle the LWRF case

Sierra Club, Earthjustice, West Maui Preservation Association, and Hawaii Wildlife Fund representatives present petitions signed by 15,962 individuals asking the County Council to settle the LWRF case

On Wednesday, Sierra Club and the Surfrider Foundation delivered two petitions to Council Chair Kelly King signed by more than 15,000 members nationwide, who urged Maui County to settle the case and withdraw the appeal from the Supreme Court.

“The county’s refusal to protect an ecosystem in our backyard could jeopardize public health and clean water across the country,” said HWF executive director Hannah Bernard. “A Supreme Court ruling in the county’s favor would have serious negative impacts on water quality nationwide.”

But to some, like Mayor Michael Victorino, the matter is less about national implications and more about immediate impacts at home. “Staying the course with the county’s US Supreme Court appeal protects our county and taxpayers,” wrote Victorino in a recent Community Voices piece for Honolulu Civil Beat, referencing not only the settlement but potential liabilities if the county loses. “[Staying the course] allows the county to continue to manage its recycled water disposal in the most environmentally and economically responsible way now available and feasible.”

“Staying the course,” however, also means continued seepage of effluent into Maui’s already stressed marine ecosystem. Despite the mayor’s comment that “A short online search shows photos of fish, sea turtles and a coral reef that appear to be in relatively healthy condition at Kahekili,” an actual peer-reviewed 2019 study in Nature found that “corals living within the [submarine groundwater discharge] seep area are impacted by sewage-effluent injected at the LWRF.”

These impacts included “nitrate concentrations up to 50 times higher than ambient seawater, and lower pH bottom water,” the study’s authors found, in addition to “lower calcification rates and increased bioerosion in corals collected adjacent to the seeps.”

Regardless of your definition of “point source” and “water of the United States,” the sickness and death of coral will affect us all, ecologically, economically, and culturally.

“We are stealing the future generations’ relationship to those animals and plants and those practices,” said Rhiannon Chandler-‘Iao, executive director of Hawaii Waterkeepers. “We are preventing the transmission of cultural knowledge from one generation to another when we lose our coral reefs and all the marine life that they hold. To me, that’s a big enough reason to settle this case here at home, as if there wasn’t life at stake on the Continent.”

Whether the public and councilmembers see it the same way is yet to be shown. The matter of the County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, and whether the county should continue litigation at the US Supreme Court or settle with HWF will be taken up at a Sep. 3 meeting of the Government, Ethics and Transparency Committee of the Maui County Council. For up to date information on the County Council’s agenda, visit Mauicounty.us/agendas/

–

Cover design by Albert Cortez

Image 1 courtesy Earthjustice

Image 2 courtesy Marley Rutkowski

Image 3 by MauiTime

Original article URL:

https://mauitime.com/news/politics/county-of-maui-v-hawaii-wildlife-fund-the-lawsuit-against-maui-county-being-watched-around-the-country/